Large Price Fluctuations Impact Food Markets

In this article we take a look at the impact COVID-19 has had on the food market over the first full year of COVID-19, how those across the industry have reacted in response, and steps that lenders can take to minimize downside risk among their food portfolio companies in the current environment.

In our previous food industry perspective article early last summer, we discussed our expectation that the wholesale food channel would be significantly impacted by COVID-19 throughout 2020. These impacts did, in fact, occur but at a lesser level than we might have expected at that time. That said, it is worth noting that from 2019 to 2020, food prices increased an average of 2.6%. In April 2020, the consumer price index for food saw its largest month-to-month increase since 1974, rising 2.7% compared to a mere 0.5% in March.

On the retail side, business has been booming, with consumers cooking and eating more meals at home by necessity throughout the pandemic. Interestingly, 71% say they will continue to do so after the crisis ends, according to a 2021 survey by consumer market research firm Hunter. This trend has led to a common misconception that grocers are raking in large profits. Grocer costs, however, have increased significantly during the pandemic period; therefore, revenue falling to the bottom line has been less than one might think. Among the many factors contributing to this have been the increasing cost of acquiring product, as well as costs associated with modifying and cleaning stores to meet COVID-19 safety standards. Staffing issues and personnel cost increases have abounded as well; many workers sought employment elsewhere and exited grocery jobs during the pandemic for reasons including concerns over exposure, prior to availability of vaccines for essential workers.

On the wholesale side, food sales, understandably, have declined notably during the COVID-19 crisis. Sysco Corporation, for example, reported a year-over-year sales decline of 12.0% for the 12 months ended June 30, 2020, and a 23.1% revenue decline for the final quarter of the year. Meanwhile, US Foods reported a sales decrease of 29.2% for the second quarter 2020, year-over-year, and a net sales decrease of 11.8% for the 12 months ended January 2, 2021, year-over-year.

Wholesalers whose pre-pandemic businesses models included both foodservice and retail sales have fared better than those singularly focused on foodservice. Those that were able to pivot quickly, to provide product needed at retail due to increased demand, were also able to counterbalance losses, to varying degrees, on the wholesale side.

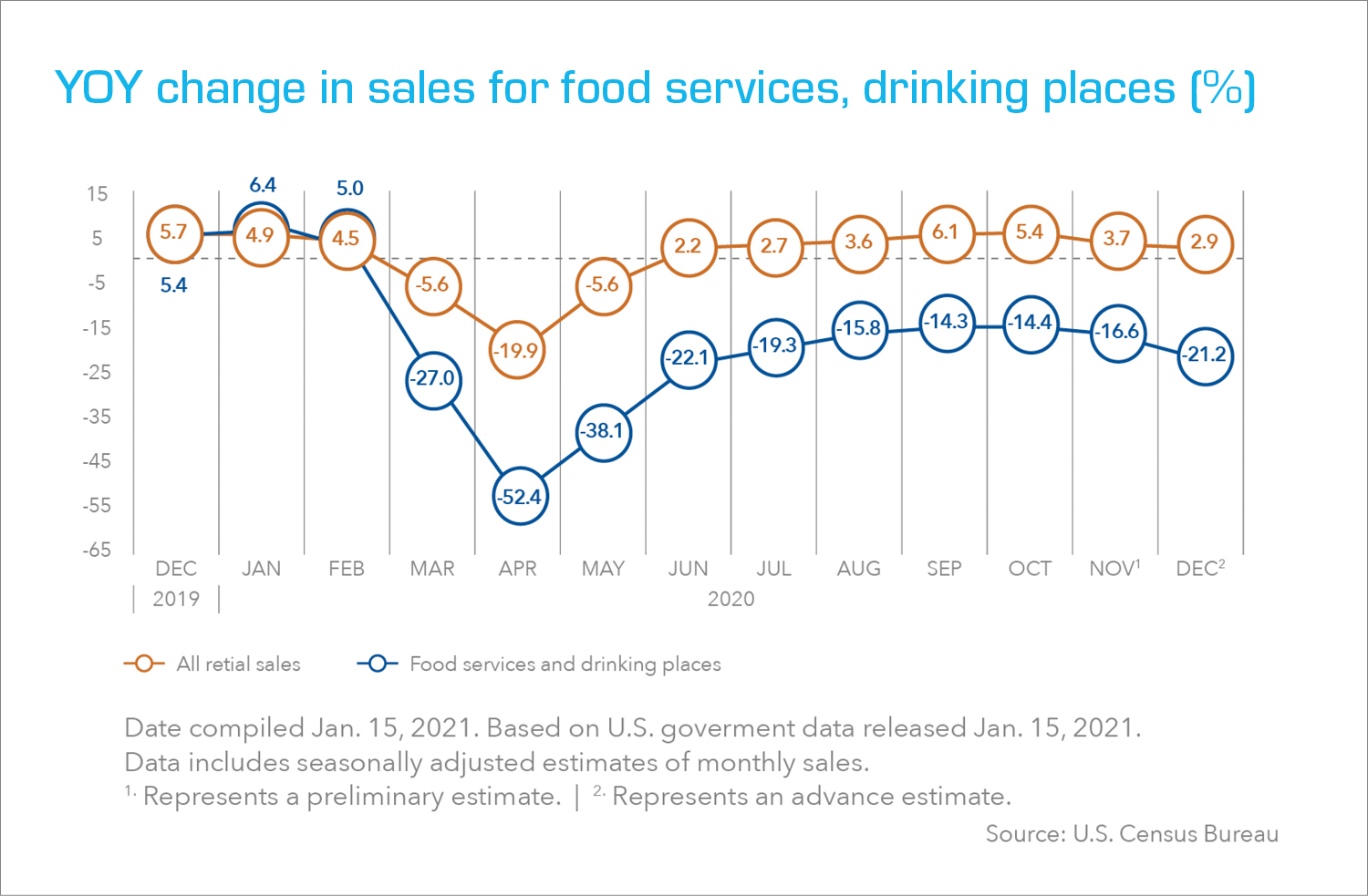

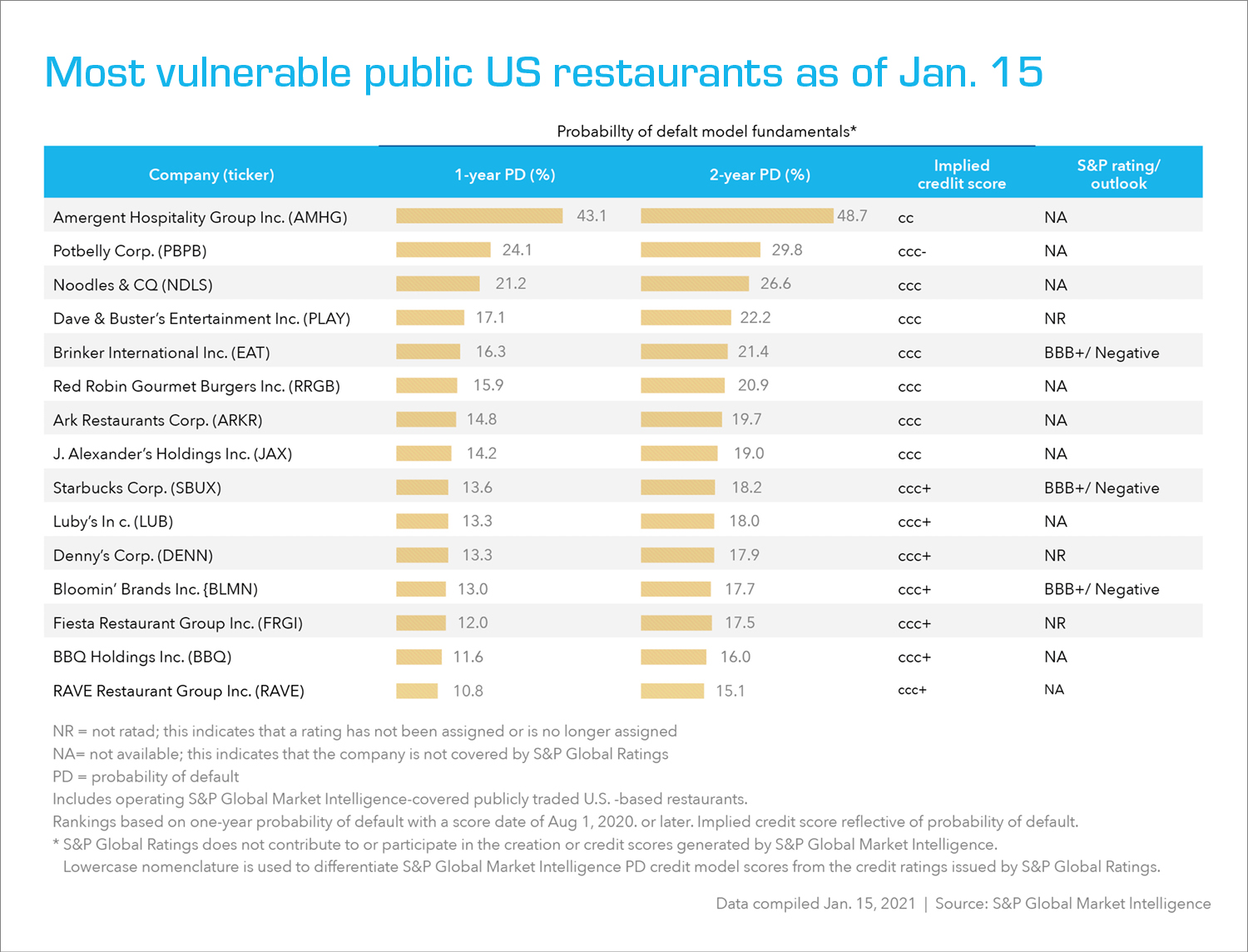

Based on feedback from Hilco’s numerous industry contacts, we believe restaurants with limited delivery and takeout capacity declined substantially greater than the 52.4% low indicated in the U.S. Census Bureau chart above during the early months of the pandemic (April). With such a significant portion of the wholesale channel driven by restaurant volume, sales have rebounded as these establishments continue to reopen and expand capacity. Despite a dip in the fall, particularly in areas such as southern California and New York, where governors imposed stringent statewide restrictions in reaction to spiking COVID-19 infection rates, the National Restaurant Association (NRA) expects restaurant sales to grow 10.2% in 2021 but still end at approximately 15% below 2019’s pre-pandemic levels. Eating and drinking establishments are expected to reach $548.3 billion in aggregate sales. According to a report issued by the NRA in January 2021, much of the momentum is expected to be driven by consumer demand for long-awaited time out of the house at establishments that they were unable to frequent during 2020, and will clearly be a welcome improvement from the 19.2% drop experienced in 2020. Based on the report, the increase should be even slightly stronger for full-service establishments, for which sales fell 30% in 2020. Last year, 83% of American adults surveyed indicated that they were not eating in a restaurant as often as they would like. That said, some experts estimate that up to 250,000 U.S. restaurants could still fail by the end of 2021.

PROCESSING

In our previous article, we expressed concerns regarding the potential for ongoing processing facility closures. In summer and fall 2020, there was a high relative incidence of workers contracting the virus, and staffing/work attendance issues were problematic. Processor compliance with distancing requirements on the production line also led to reduced efficiency. Production, however, remained relatively stable, declining only .02%, year-over-year, as of November 2020. With the essential worker designation and the availability of various COVID-19 vaccines starting in late 2020, the trend has improved in the first quarter of 2021.

Beef/Pork

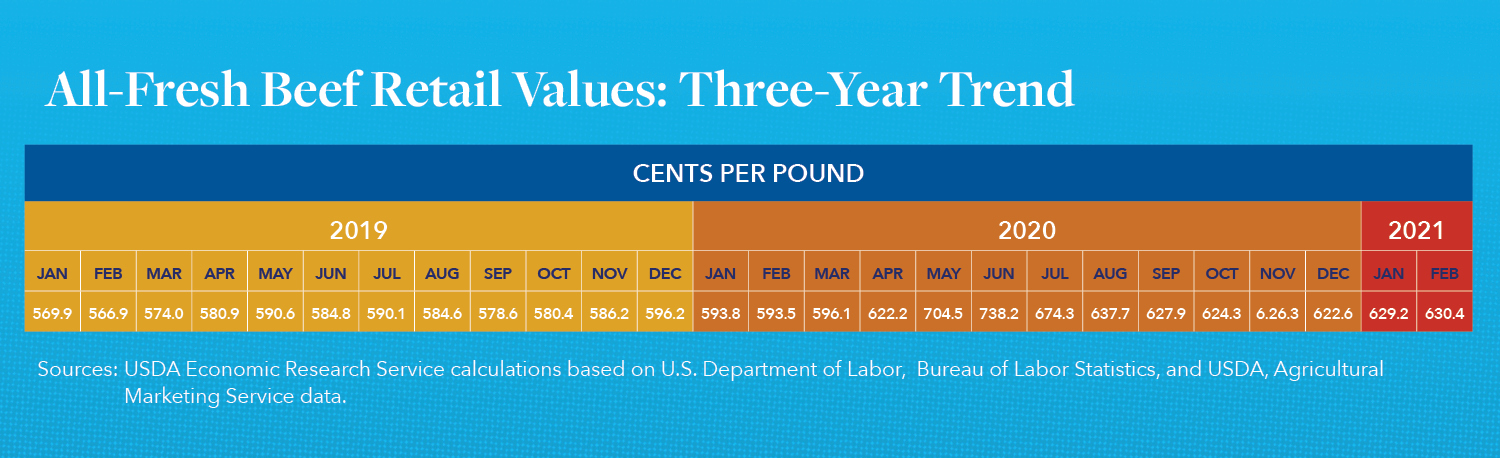

Beef pricing, which averaged 581.9 cents/lb. during calendar year 2019, spiked in the early months of the pandemic, hitting 738.2 cents/lb. in June 2020. From August 2020 through February 2021, prices remained stable, averaging 628.3 cents/lb. As of February 2021, prices were 6.2% higher than the prior year. Price increases were primarily due to stockpiling, as there were no major facility closures that limited production during that period and no major beef or labor shortages, despite COVID-19 restrictions. Pork experienced a similar increase in demand during April through June 2020, with prices normalizing thereafter. Overall, beef and pork production was relatively stable in 2020, versus 2019, with beef down 0.6% and pork up 2.3%.

The fourth-quarter 2020 beef production forecast was raised slightly on higher non-fed cattle slaughter that more than offset lower expected cattle carcass weights. Production in 2021 was lowered by 105 million pounds on fewer expected fed cattle and cows slaughtered in the first half of the year. Weaker fed steer prices in November and early December 2020 contributed to a lower forecast for fourth-quarter 2020. However, 2021 prices have been raised $1 to a level of $115 per hundredweight on fewer fed cattle expected available for slaughter. Feeder steer prices were unchanged in 2020 and 2021. Beef imports in October 2020 were 4% above a year ago, but below expectations. This reduced the fourth-quarter 2020 forecast 40 million pounds, to 760 million pounds. The 2020 and 2021 beef export forecasts were unchanged.

Dairy

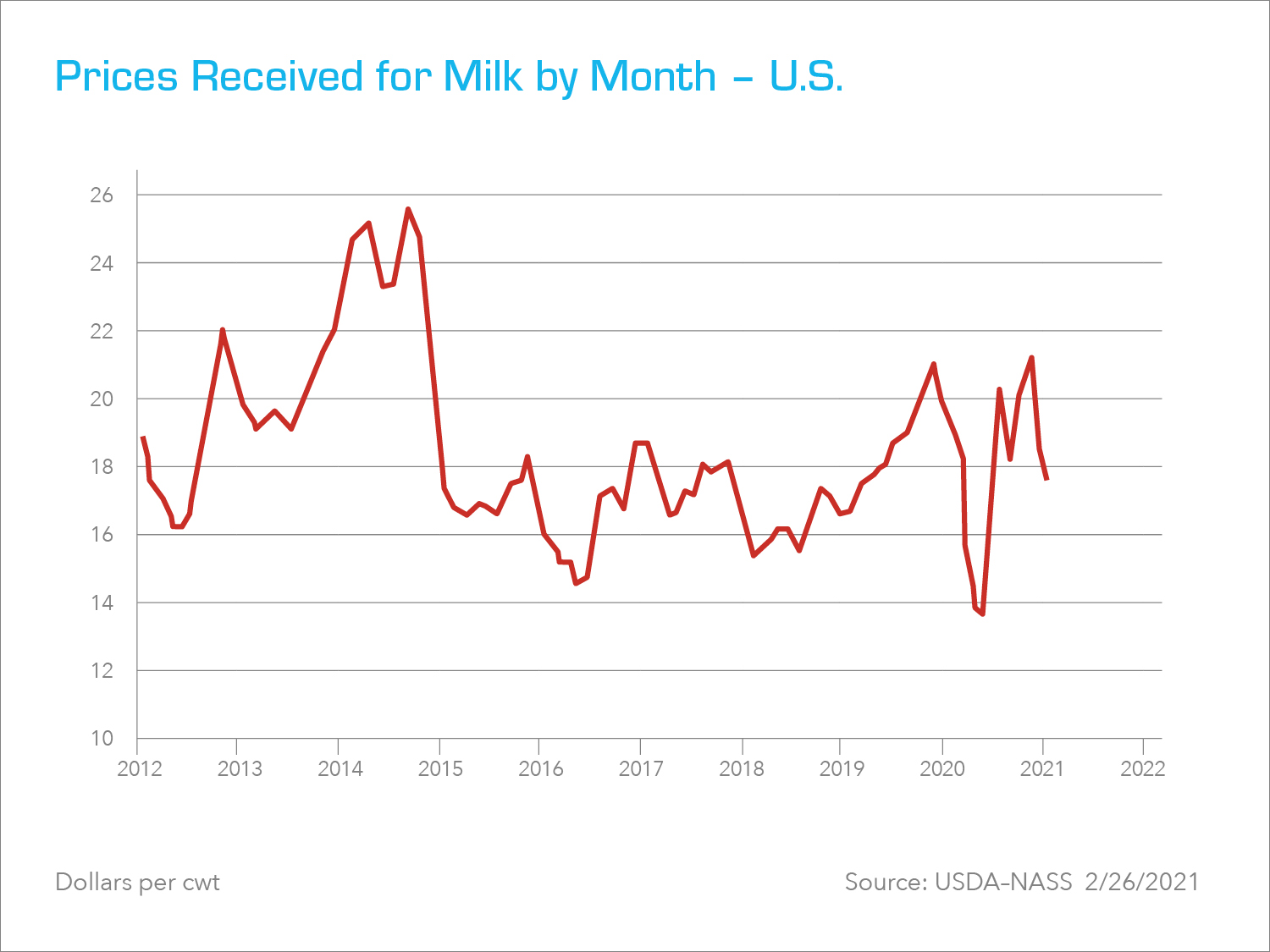

Regardless of demand, dairy farmers must milk their cows, and the resulting milk is always ready and waiting. Therefore, when milk futures, which had averaged $17.13 per hundredweight in 2019, plummeted to $10.39 on April 21, 2020, farmers paid a dear price. With the sudden drop in demand from food service providers, including restaurants and schools due to mandated COVID-19 closures, these farmers found themselves in a predicament few had thought possible just months earlier. With excess product, limited processing facilities willing to accept it, and logistics issues mounting, many were forced to dump milk. At one point, the Dairy Farmers of America estimated that between 2.7 million and 3.7 million gallons of U.S. milk were being dumped per day. Based on the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which authorized $100 million in monthly U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) purchases of dairy to be distributed through the charitable food system, July 2020 futures increased to $23.40, their highest level since 2014. By late in the year, they had dropped again, returning to pre-pandemic levels in the $17 range. With farmers expected to increase herd sizes again in 2021, USDA price estimates for 2021 are $16.60 per hundredweight. January and February 2021 data appears to reinforce that expected trend.

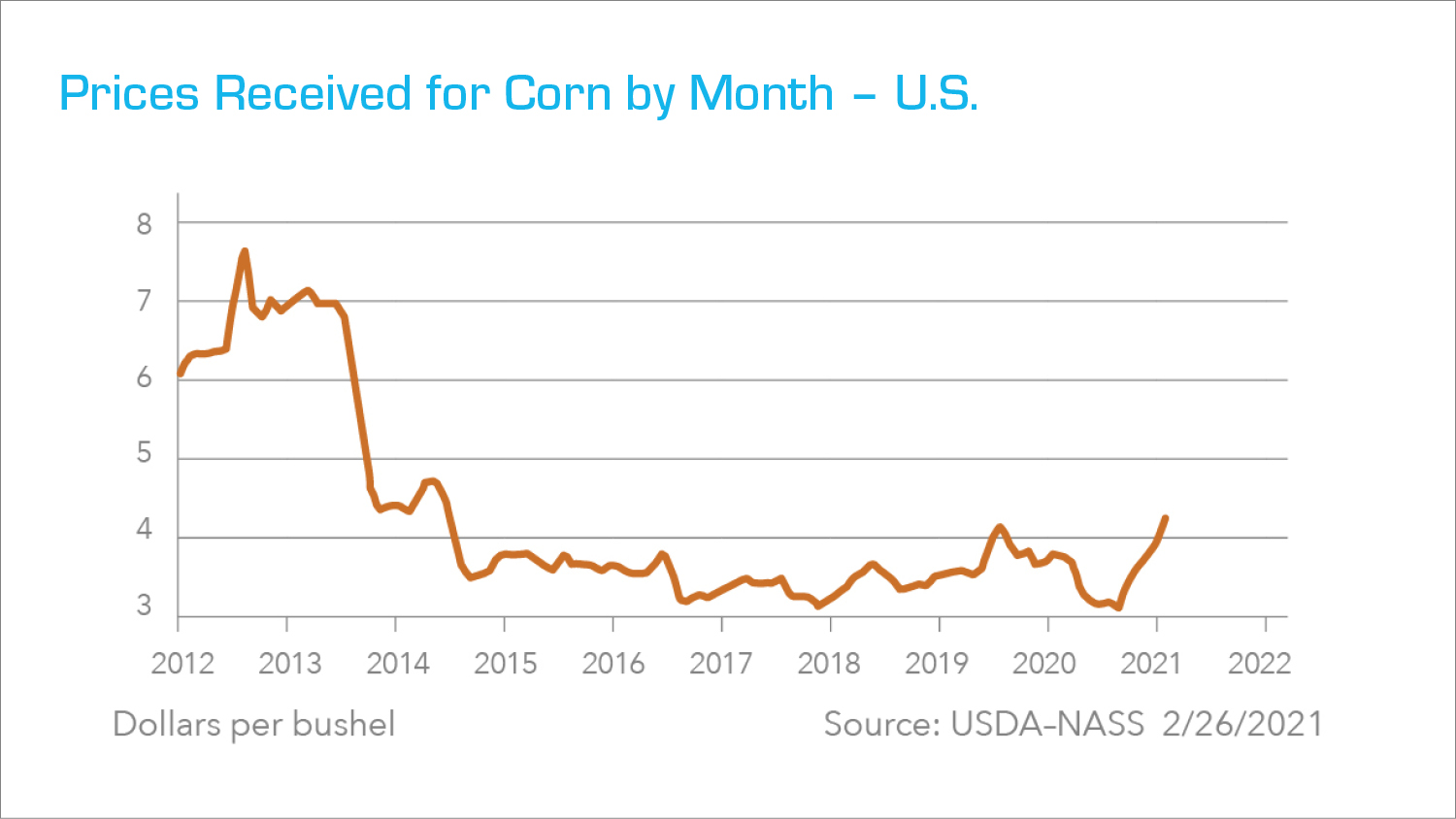

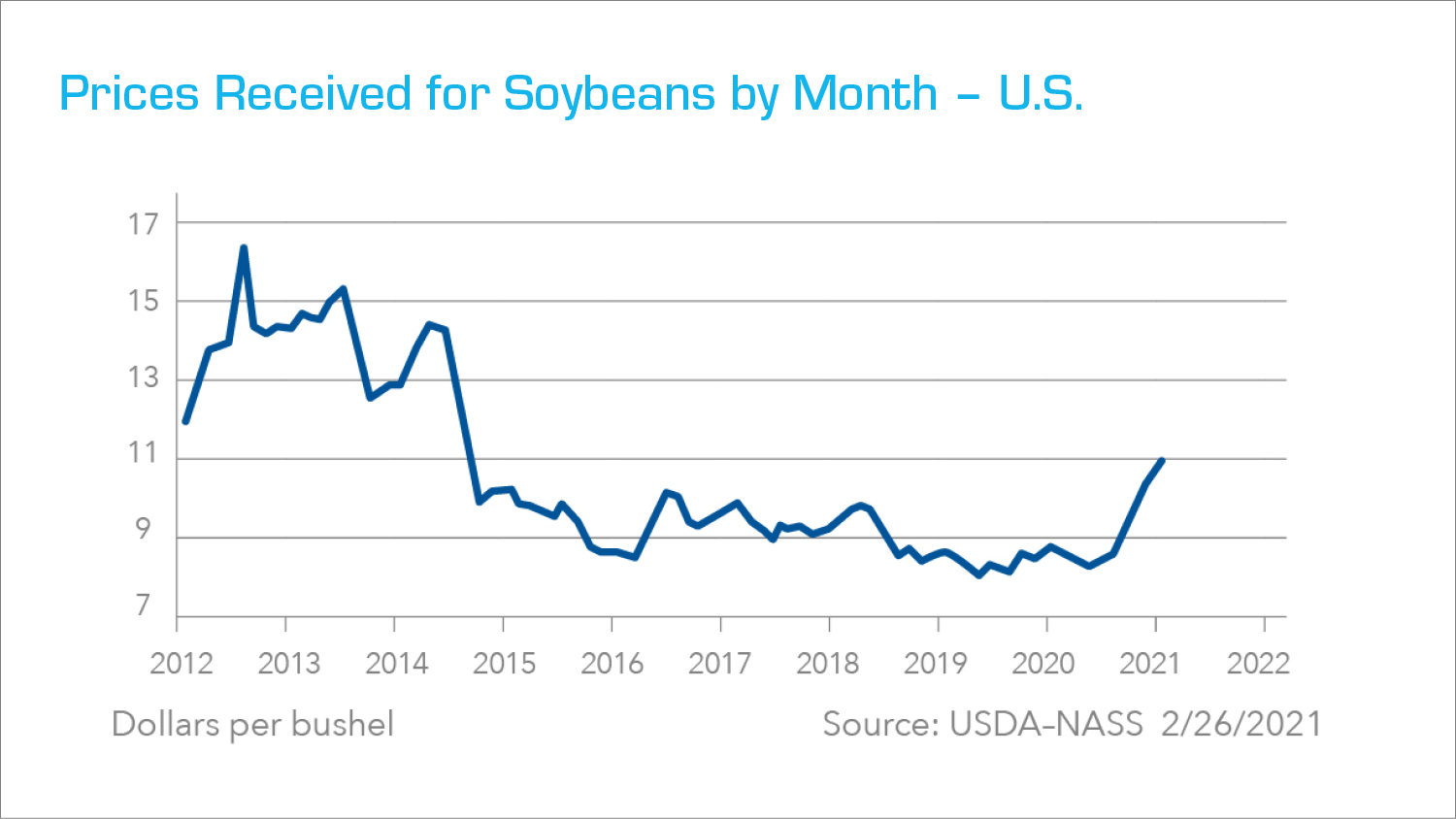

Corn/Soybean

Corn and soybean prices were not materially impacted by the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, remaining relatively stable at between $3.00 and $3.50 and between $8.00 and $9.00 per bushel, respectively, from April into August. Beginning in late August/early September 2020, corn prices began a steady increase and reached $4.92 by early January 2021. Soybean prices followed a parallel path during this period, reaching $13.47 per bushel in early January 2021. In each case, these increases were driven not by the pandemic, but rather by dry weather that month. This reduced the water weight and size of kernels and resulted in a reduced yield from harvest.

The U.S. Government has continued its subsidies for the use of corn in the production of ethanol (corn ethanol) during the COVID-19 crisis. This is significant, as 20% of the corn harvest is now used for this purpose compared with just 6% 20 years ago. However, if a fourth wave of COVID-19 occurs in the U.S., as certain European countries are experiencing, this could impact overall demand for ethanol in the months ahead.

Conclusion

Overall, a great deal of uncertainty still exists as we move ahead. On the one hand, great resiliency was demonstrated by the industry during a very challenging period for Beef and Dairy, and many players were able to pivot effectively to meet the unique challenges associated with losses in the wholesale channel.

On the other hand, most food companies will now likely look to hedge away from channel-specific dependency by bidding multi-channel work and enabling processing capacity to produce both bulk and retail varieties. Such a shift, however, comes with added capital costs and potential disruption to existing lines and production, particularly during the period of transition.

Additionally, the shortages and pricing that we are currently seeing across these commodities create significant challenges for companies that have existing contracts to supply volume, as they either need to go out and acquire that capacity or trade for it to ensure that they can continue to supply their customers. Failure to do so could result in damaged industry relationships, as well as the loss of lucrative long-standing contracts and the associated revenue to competitors.

With all the price changes that have been occurring, it is extremely important to understand the impact on Net Orderly Liquidation Value (NOLV) and the associated borrowing base certificates in place. For example, if a borrower is selling primarily through wholesale channels, the downside impact from the current crisis is likely to have been far more significant than in cases where a borrower’s sales are focused on other producers or retail, where business has remained strong throughout the pandemic.

Hilco encourages lenders to take steps now to update existing appraisals for their food portfolio companies, particularly those affected by the major price swings we have seen in corn and soybeans over the past year. Furthermore, given the likelihood of continued volatility in the industry, we recommend increasing appraisal frequency to quarterly intervals for the foreseeable future. We view this step as an important part of limiting downside risk for lenders in the current environment.

With numerous client engagements currently in progress and conversations occurring with our contacts across the food industry and the asset-based lending community every day, we continue to gain new insights and perspectives that can help us assist our clients. In the months ahead, we encourage lenders to work hand-in-hand with their food portfolio companies to gain a comprehensive understanding of the distinct challenges those businesses could be facing a year into the pandemic. Please reach out to our team if we can be of assistance to you in these efforts or in any other way, either today or in the weeks and months ahead. We are here to help.