Food Industry Grappling with Challenges and Uncertainty of Recovery Timeframe from Global Pandemic

In this article we look at how pandemic-driven business closures, ensuing consumer purchasing behavior and supply chain dynamics are impacting the retail, production, distribution, and foodservice segments

of the food industry.

The COVID-19 crisis has changed the way consumers shop and purchase food products. With restaurants closed to sit-down service and providing only delivery or takeout, customers have turned to retailers and grocers to fill in the gap for their food consumption needs.

The impact of the current situation on those in the food industry varies both by state, based on the extent and timing of each governor’s shutdown orders, and by sales channel. For those selling through online and retail channels, for example, business has been booming. According to Entrepreneur, Amazon is reporting a 60% increase in demand for grocery delivery and pickup and, as a result, announced on April 13 that it would stop accepting new customers for these services, instead adding them to a wait list.

Businesses selling through foodservice, however, are experiencing quite a different reality in the current environment. Here, due to the widespread closure of restaurants, schools, corporations, sports, and other venues, the business drop-off is dramatic and, in some cases, could be catastrophic depending on when the pandemic curve begins to decline and states begin to lift restrictions on dine-in restaurant operations.

Food Retail

For retail, the boom started in mid-February in the U.S. as awareness of the coronavirus began to heighten among the general public. Retailers were not prepared for the increase in volume they began to experience and had inventory levels consistent with norms of approximately two weeks’ supply on average (less for fresh produce). Warehouse club behemoth Costco Wholesale Corporation (Costco) saw sales increases of 12% in early February, which escalated to 28% by the end of that month. The Kroger Company (Kroger) was up even more, with an increase of 30% for March.

While much of this increase can be attributed to stockpiling based on generalized uncertainty and fear, significantly more people now are eating multiple meals in the average American home. Parents are working from home, and children are attending school remotely from home.

For April, we expect to see an overall decline in revenue at retail from the previous month’s highs, as most back stocks have been filled, and many stores are limiting the number of people allowed inside, as well as the number of certain products (e.g., antibacterial sprays and toilet paper) they may buy at one time. Still, revenue is expected to remain higher than in 2019 due to severely limited restaurant options and shelter at home requirements.

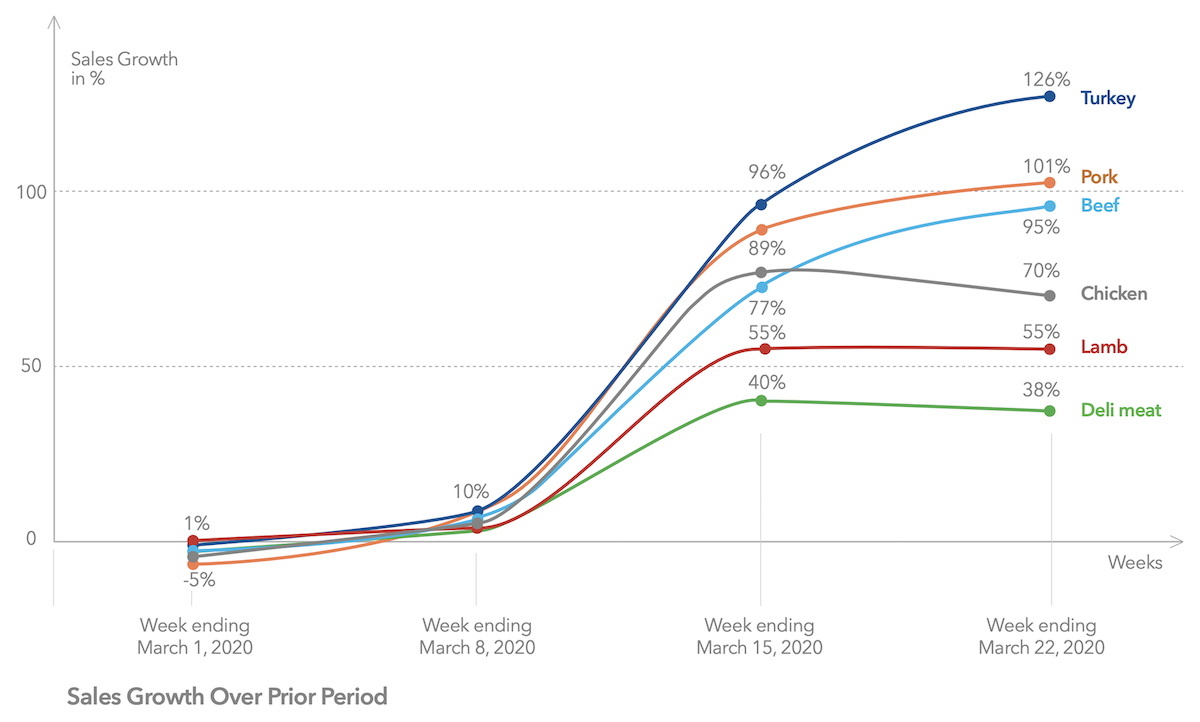

For the week ending March 22, 2020, the number of trips to grocery stores and supermarkets increased 39%, and during each trip, consumers purchased about 12% more items, and spent, in aggregate, about 61% more as compared to the same week one year prior. Fresh meat and frozen food sales led the increase in dollar sales. Pork sales increased 101%, beef sales increased 95%, and chicken sales increased 70% for the week ending March 22, 2020 as compared to the same time period in 2019.

As retailers reap record high profits, workers are demanding pay increases to compensate for increased risk. Retailers including Target Corporation (Target), Kroger, and Costco have acted to increase hourly pay. At the same time, food delivery services such as Instacart, Shipt, Walmart Grocery, Target and their associated apps have seen significantly increased volume and new user adoption, as consumers seek to purchase more delivered foods to minimize personal exposure risk.

Near-term risks to retail food operators resulting from the current crisis include: 1) further increased demand that cannot be met for pickup or delivered products; 2) increased reported cases of COVID-19 among employees or shoppers at retail locations, which would require store closures and/or would reduce consumer traffic significantly at those locations; and 3) employee shortages due to mass infection or sickouts that, even with the increased hiring by retailers, pose additional challenges for an already stressed system.

Foodservice

Prior to COVID-19, foodservice was a $280 billion industry in the U.S., employing some 350,000 workers. The question is, what will it look like when the fallout from this pandemic has ended? The largest foodservice companies – Sysco Corporation (Sysco) and US Foods Holding Corp. (US Foods) – have experienced massive sales reductions since the start of the crisis due to closures and lower volume at those operations that remain open; this is not surprising, considering, for example, that restaurants represent more than 60% of Sysco’s sales. The situation has become so significant that Mark Allen, President of the International Foodservice Distributors Association (IFDA) wrote to President Trump stating, “COVID-19’s economic impact on the foodservice distribution industry is dire and requires immediate attention from the Trump Administration.”

While some might perceive this as yet another bailout plea that the U.S. government should reject, the fact is that the foodservice platform in the U.S. supports vital infrastructure, such as hospitals and eldercare facilities, as well as the military, the correctional system, and the government itself. Beyond fulfilling these needs, we currently are seeing many foodservice distributors (e.g., Sysco and US Foods) pivot to support the retail market via their relationships. These efforts are being fostered through partnerships between IFDA and the Food Marketing Institute (FMI) designed to supply extra product and transportation. Additionally, US Foods has partnered with C&S Wholesale Grocers, the largest wholesale grocery supplier in the U.S.

With restaurant transactions plummeting 41% during the week ended April 5, year-over-year, according to the NPD Group, some shuttered chains and independents are getting creative in driving revenue to help pay rent and support staff. Panera Bread, for example, is selling groceries (e.g., breads, bagels, milk, cream cheese, and a variety of fresh produce) that it typically procured and prepared for dine-in and take-out restaurant customers. Groceries can be ordered on the company’s app or website, or via delivery service Grubhub, and either delivered or picked up at a Panera location. Separately, the Frish’s Big Boy chain has taken to leveraging its access to staple items that are in short supply at retail (e.g., toilet paper) by selling these directly to consumers through its many restaurant locations.

The unfortunate reality, however, is that even with the additional volume generated through these and other creative efforts, we still expect sales levels to be down quite significantly for the foreseeable future.

Producers, Packaging, and Distribution

Across the supply chain, those in the food industry are facing significant challenges. For food producers, these include the acquisition of materials as well as the personnel to produce, package, and distribute products. In the case of milk, for example, both demand and prices are up significantly. Retail purchases of milk rose nearly 53% for the week ended March 21, while the average retail price of milk for that same week was up 11.2%, year-over-year, according to Nielson data.

Across the supply chain, those in the food industry are facing significant challenges. For food producers, these include the acquisition of materials as well as the personnel to produce, package, and distribute products. In the case of milk, for example, both demand and prices are up significantly. Retail purchases of milk rose nearly 53% for the week ended March 21, while the average retail price of milk for that same week was up 11.2%, year-over-year, according to Nielson data.

Across the supply chain, those in the food industry are facing significant challenges. For food producers, these include the acquisition of materials as well as the personnel to produce, package, and distribute products. In the case of milk, for example, both demand and prices are up significantly. Retail purchases of milk rose nearly 53% for the week ended March 21, while the average retail price of milk for that same week was up 11.2%, year-over-year, according to Nielson data.

Notably, however, the industry – which also includes butter and cheese processing plants – is one of the most negatively impacted, as the products are highly perishable and cannot be frozen or stored for long periods of time.

Dairy cooperatives are responsible for sales, marketing, and logistics management for farmers. In turn, many of these co-ops rely heavily on the foodservice market for sales channels, which include exports. In recent weeks, the Dairy Farmers of America and Land O’Lakes have required many farmers to dump their milk due to the inability to process and ship it to end users expediently. News footage of these incidents has shocked and confused consumers, many of whom have experienced empty or sparsely stocked dairy cases in their local grocery stores.

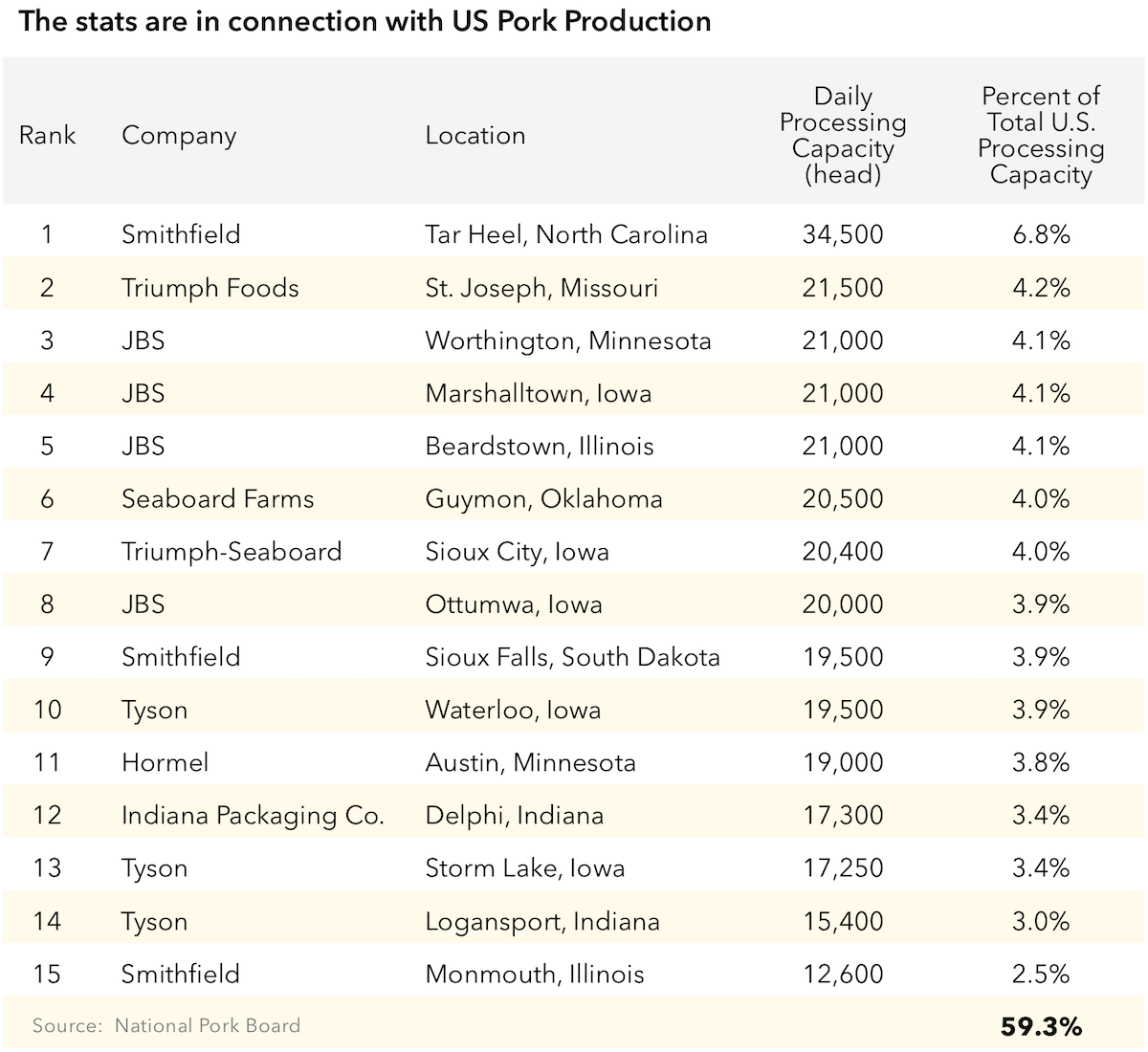

In a press conference on April 15, U.S. Agricultural Secretary Sonny Perdue cited the efforts of critical, essential food supply workers, including farmers, producers, processors, truckers, and grocery store workers in providing food to American families, referring to them as true patriotic heroes. “The bare store shelves that you may see in some cities in the country are a demand issue, not a supply issue,” he said. “Our supply chain is sophisticated, efficient, integrated, and synchronized, and it’s taken us a few days to relocate the misalignment between institutional settings and grocery settings. But that does not mean that we don’t have enough food in this country to feed the American people.” His comments came just six days after Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest pork processor, shuttered its South Dakota plant after it revealed that 238 employees at the facility had active cases of COVID-19. The proximity of workers in food production facilities can breed coronavirus infections. JBS shut down three facilities, and Tyson Foods announced it will close two locations.

The U.S. has capacity to slaughter more than 500,000 pigs p/day with almost 60% of that capacity coming from just 15 plants, the majority of which are either currently closed or have confirmed cases of COVID-19.

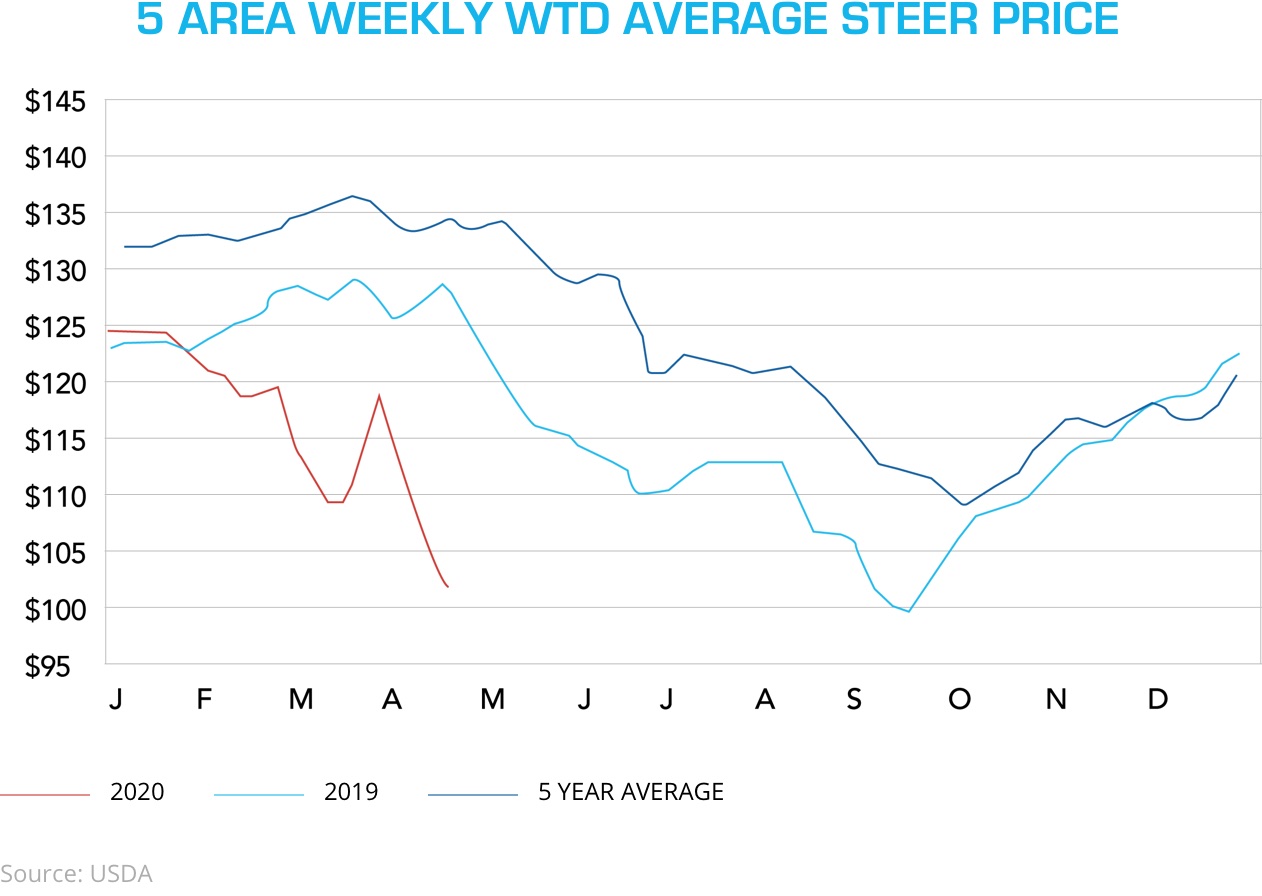

The average U.S. steer price has fallen significantly in April, and remains well below ahistorical selling prices.

Supply Chain Ramifications

Inventory:

With warehouse closures, related furloughs, and significant quantities of perishable inventory on hand, we expect to see product with expiration dates in the next 6 to 12 months make their way to the market via secondary players that specialize in selling distressed food products.

Shipping:

Most imported food is carried via container ships, and imports from China into the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach have declined approximately 20%. Shipping issues are most impactful to product with a short shelf life (e.g., fresh produce).

Labor:

Labor shortages could disrupt supply chains for planting and harvest seasons. Common crops that require little manual interaction (e.g., wheat and rice) should present fewer challenges. However, those crops that require a higher degree of manual labor (e.g., apples or strawberries) could experience difficulties. Trained labor could be difficult to hire due to travel disruptions, and social distancing could decrease efficiency and increase costs. Further down the road, a lack of farm maintenance due to a diminished and insufficient workforce could create losses in future seasons.

Outlook

While the food industry is certainly not alone in facing significant current and future challenges as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, vast fluctuations in supply and demand in the industry are likely to lead to further price instability and sell-through issues. This will have an impact on food products downstream, which, in turn, could drive recovery values. From meat (where more than 20% fewer cattle were slaughtered during the week of April 13, year-over-year) to frozen pizza and frozen fruit (where fear is driving excessive customer stockpiling), processing and packaging capacity is becoming stressed. Despite official government statements to the contrary, there is justifiable cause for concern pertaining to certain segments of the near- and mid-term food supply.

Understandably, in this extraordinary climate, many of our asset-based lender and corporate clients across the industry spectrum are working to understand the inherent risk among companies in their portfolios through stress testing, modeling, and other efforts. Throughout this highly unpredictable and volatile period, Hilco Valuation Services recommends that lenders, including those with exposure in the highly impacted areas of retail and foodservice, undertake more frequent appraisal updates on their portfolio companies to assess recovery values and assist in gauging overall risk. With the most accurate valuation analysis and expertise in the industry and a highly experienced and proven food industry practice that spans processing, importing, and distribution, Hilco is ready to assist you and your institution in this process. Give us a call today. We’re here to help!