How Sellers of Intangible Assets Can Benefit From Bespoke Auction Design

(As seen in the ABI – American Bankruptcy Institute)

This article discusses how sellers of intangible assets, and their advisors can tailor auction design in order to maximize auction proceeds.

Auctions are a popular method for liquidating intangible assets in insolvencies, both in and out of court. These assets include patents, trademarks, domain names and software, all of which frequently appear in restructuring cases. For professionals responsible for liquidating intangible assets, auctions meet several objectives that are difficult to achieve in a private sale. First, auctions often create a credible and public market test of value. This is extremely important in cases where there are few comparable sales reported publicly. Second, the speed and certainty of an auction can help maintain a desired timeline or cash flow target. Third, depending on the format, auctions can be utilized to leverage the competitive tension among bidders.

For these and other reasons, auctions have earned a prominent place as a method of sale of intangible assets both in and out of restructuring situations. There are a variety of auction types to choose from and rules to consider in the design process in order to maximize auction proceeds, and the determination of which auction format to use can have a dramatic impact on the outcome.

GOALS AND HISTORY OF AUCTION DESIGN

The design of real-world auctions is informed by a branch of economics known as Auction Theory. This discipline focuses on the way in which auction design influences bidder behavior and, how information about the bidding parties and the nature of the assets for sale can influence auction design. Auction Theory is generally thought to have its roots in an article published in 19611 by the Canadian-American economics professor William Vickrey, but went largely unnoticed until years later when theorists became actively involved in work on the subject.

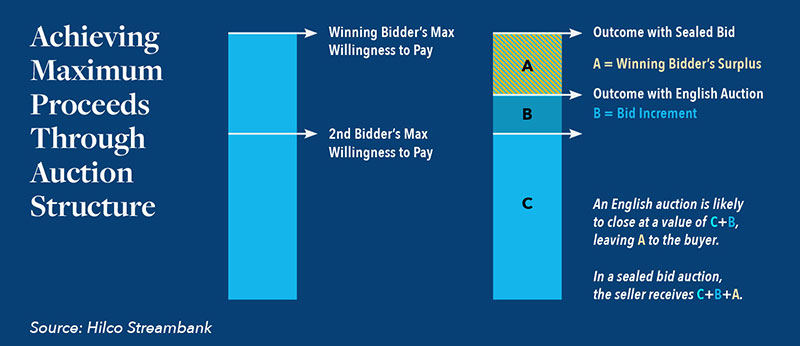

While there are a number of inputs to auction design, the primary goal remains achieving the highest possible selling price. A well-designed auction elicits each bidder’s maximum willingness to pay, minimizing what economists refer to as “consumer surplus” or the difference between a buyer’s willingness to pay and purchase price. For example, Haley and Josh are each bidding on an item at an auction where bid increments are a minimum of $10. Haley is willing to pay $500 and Josh is willing to pay no more than $250. In a traditional English style auction, the auctioneer would start the bidding and the two bid against each other until either Haley or Josh bids $250. If Haley bids $250 first, that will be the selling price. If Josh bids $250, Haley will raise by $10 and win. This leaves $260 for the seller and Haley retains $240 of consumer surplus. Effective auction design, however, can be leveraged to extract greater value from Haley. As discussed below, skilled auctioneers utilize information they develop over the course of a sale process to devise an auction structure which results in a better seller outcome.

INPUTS TO AUCTION DESIGN

Optimal auction design requires a thorough understanding of:

• The nature of the asset.

• The likely types of potential buyers.

• The potential buyers who have been brought to the table.

• Strategic considerations among.

those particular potential buyers.

Assets are typically described somewhere on the spectrum of a perfect commodity (nearly identical asset, many buyers, many sellers, low transaction costs, etc.) to unique assets that are irreplaceable, such as a Renoir painting. While certainly not irreplaceable in the way a Renoir painting is, intangible assets are unique and often require bespoke auction structures to maximize value.

Likely buyers for any asset are often categorized as strategic or financial. Strategic buyers are typically those operating in the same industry or selling to similar customers. Financial buyers are typically driven purely by the potential investment returns and are always choosing among alternative investment opportunities. These characterizations are not static because a potential buyer’s own valuation or bidding strategy may depend on the other participants at the start of the auction, or which remain as the field of bidders shrinks. Even among purely financial buyers, understanding the valuation models and historic investments of those types of potential bidders may help with auction design.

Understanding the strategic considerations at play is extremely important as well. Are the potential bidders in the same specific business? Do any of them view the others as competitors? Is that view reciprocated? What have the potential bidders revealed about their willingness to pay for this asset or similar assets? What are the use cases for the assets for each potential bidder? In the case of patents, are any of the potential bidders worried about future litigation (i.e., are they infringing but have not yet been sued?), or are they interested in the intellectual property to help resolve current litigation matters? When it comes to maximizing value in a timebound process culminating in an auction, it is the selling agent’s responsibility to obtain as much of this information as possible in order to design a value maximizing auction.

AUCTION DESIGNS

There are many auction structures that can be leveraged in a sale of intangible assets based on these considerations. They include:

• Dutch/ Descending Price Auction: an auctioneer starts with a very high price and lowers that price in defined increments until one bidder accepts the offer. In the example above, Haley should raise her hand at $500, and would win.

• English/Ascending Price Auction: as described in the earlier example, the offer price increases until there is only one bidder left. Participants in English auctions are able to gather information about the other bidders more quickly than in a Dutch auction, and have the opportunity to raise their bid until there is a clear winner.

• Sealed Bid/Second Price Auction (Vickrey): the bidder with the highest bid pays the amount of second highest bid. It is a widely held belief that in these Second Price auctions, bidders will reveal their maximum willingness to pay because they are guaranteed to retain some “surplus” in the event that they win.² This type of auction is commonly used when sellers are conducting many auctions with the same buyer group as a price discovery mechanism, such as with online advertising. In our two person example, Haley would win at $250 and retain the rest as her surplus.

In patent sales, many participants do not wish to be identified because doing so could make them a possible litigation target. In some cases, bidders for patent assets may believe an anonymous participant is a direct competitor and this may cause them to increase their maximum willingness to pay. Paranoia can quickly transform a financial buyer to a strategic buyer in the middle of an auction. At charity and collectors’ auctions, for example, factors such as reputation and competitive “oneupmanship” are often at play. These same factors are often present in the sale of intangible assets, particularly among industry competitors. In cases such as these, having the right combination of potential bidders involved can turn ego into value for the seller.

CASE STUDIES

The following case studies highlight how sellers can utilize bespoke customization of auction structures to maximize the value of intangible assets.

In Johnson Publishing Company’s Chapter 7 bankruptcy case (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 19-10236), the crown jewel of the estate was the photography and media archive from the company’s two signature magazine titles, Ebony and Jet. The archive contained over one million photographs chronicling African American life, culture and history over a 70-year span. A disparate group of potential buyers conducted diligence on the archive. The archive clearly had financial value to entities engaged in the business of image licensing. There was also an interesting tax arbitrage opportunity for creative financial buyers, as it seemed likely that the purchase price would be less than the tax savings from a future donation at a higher appraised value.

There were also buyers whose interests were not explicitly financial, such as museums and research institutions. Their willingness to pay was based on a variety of factors, including available funds, the “trophy” nature of the asset, the ability to use the acquisition as a fundraising tool and the ability to attract follow-on research grant funds. On the one hand, these institutions may have viewed each other as strategic competitors. On the other hand, if one or more of the institutions was unable to commit sufficient funds to the acquisition, they may have viewed each other — and other bidders — as potential partners. One of the qualified bidders was the secured lender, a family office that had adjacent investments and interests. Lastly, foundations which had been known in the past to acquire art and artifacts related to specific areas of their interest participated in the process.

The auction began as a typical English style auction, below the secured lender’s loan amount. Although the secured lender had not agreed to sell at a value less than its loan amount — it would have simply credit bid — it agreed with the strategy to “warm up the crowd” by starting low. When the auction got to the point where the secured lender’s debt was cleared, the Trustee pivoted to a sealed bid auction with best and final bids, which yielded a winning bid of $30 million, roughly twice the secured loan amount.

In Circuit City’s bankruptcy, Hilco Streambank conducted a sale process for the company’s brand and internet assets as well as its customer files.

The determination to switch formats was based on the inherent uncertainty about how the remaining participants viewed each other, combined with the nature of this unique asset. Did the family office really want to own this trophy asset? Did the foundations not want these assets to possibly disappear from the public eye for another 70 years? Did the participants believe the others to be a likely good steward of the asset and would each one be content if it lost the auction? Was ego involved? Based on the answers to these questions — answers which only the Trustee and her advisors had (or didn’t have) — the Trustee moved to a sealed bid format, where it was most likely that the bidders could not accurately guess the intent of the others and bid accordingly.

In Circuit City’s bankruptcy (Bankr. E.D. Va. 08-35653), Hilco Streambank conducted a sale process for the company’s brand and internet assets as well as its customer files. This process took place after the stores had been liquidated and the e-commerce site had been shuttered. The company identified and designated a stalking horse bidder, and began a six-week effort to bring topping bids to the table. All of the qualified bidders brought to the auction operated businesses similar to both Circuit City and the stalking horse. At the auction, the stalking horse and two others quickly emerged as strong contenders. The bidding cadence started rapidly, with bids increasing at amounts higher than the stated minimum increment, until one bidder asked for a break to get authority to bid even higher. Ultimately, after several more rounds of bidding, one bidder reached its maximum and declined to place further bids. The second place bidder raised by one increment, and was immediately outbid by the stalking horse. There was no additional bidding. In post-auction conversation, it became clear that the second and third place bidders each viewed the other as a competitor but neither had been troubled by the prospect of losing out to the ultimate winner. The winning bidder who viewed both of the other bidders as competitors had stayed in the auction for strategic reasons. Had either the second place or the third place bidder not been present at the auction, the other would likely have not placed a single bid. The decision to commit to an English auction based on the perceived competitive nature of the bidders proved to be the right decision. It was the third place bidder’s continued participation that drove up the hammer price. The final selling price was 3 times higher than the stalking horse bid.

In an Article 9 sale conducted on behalf of a secured lender of a borrower whose primary asset was a patent portfolio, the strategic considerations of the pool of potential bidders were largely unknowable. The chosen auction structure involved a succession of sealed bids by parties who were required to remain anonymous. The auction process started with an opening sealed bid round, submitted by email. At the end of the round the value of the highest bid was announced, and the lowest bidder — whose bid amount was not identified — was eliminated. This process repeated itself until there was only one bidder remaining. The goal of this approach was to increase the chance that bidders viewed their involvement in the process as strategic but also to cause them to disclose values close to their maximum willingness to bid. Conversely, the use of an English auction in this circumstance would have run the risk that none of the participants viewed other bidders as strategic, and the high bidder would have acquired the asset for much less than its ultimate purchase price. In the end, the auction resulted in a value which not only fully paid the secured lender, but also left the company with enough cash to wind down its affairs.

CONCLUSION

Every auction has its own dynamic. Being able to assess the inputs to that dynamic – including the unique nature of many intangible assets – and determine how best to deploy the right auction strategy are critical components that allow experienced advisors to add value by delivering a truly bespoke auction process. This involves gaining a comprehensive understanding of how the asset for sale can create value for a potential set of buyers, and then inviting those targeted buyers to participate in the process. Effective auctioneers of intangible assets utilize all of these inputs and ongoing communications with participants throughout the diligence process to learn as much as they can about each bidder, their motivations and limitations, with the goal of using that information to best determine the most beneficial auction strategies as the process unfolds.

Hilco Streambank is the preeminent intellectual property advisory firm, specializing in the valuation and disposition of all forms of intangible assets, investing in intellectual property and operating a leading brokerage business focused on IPv4 internet protocol addresses. Our work in delivering bespoke auction solutions for our clients goes hand in hand with the wide range of services and expertise we provide at the intersection of intangible assets and corporate finance. Hilco Streambank is part of Hilco Global, the world’s premiere authority on asset valuation, monetization and advisory solutions, with a reputation earned from helping both healthy and distressed companies identify and derive maximum value for their tangible and intangible assets.